Two nights ago I returned to Um Dorit, to the family at the front lines of the Zionists’ land-grab. The outpost across from them, which was a singular stationary bus when I first arrived three months ago, now has full electricity, water tanks, dozens of hay bales, and a large raised wooden foundation to its side. Construction is moving swiftly. A trailer, like the one I had classes in when my high school was being remodeled, has also appeared.

Donate to sustain the work, here!

Just before dinner, a Zionist man known locally as Budi drove up to the family’s house and stared at us with binoculars even though he was only a few feet away. He idled his engine for over half an hour. We watched him as he watched us. Nobody moved. It was truly a bizarre way to spend the evening and would have been funny if I did not know of his legacy of violence.

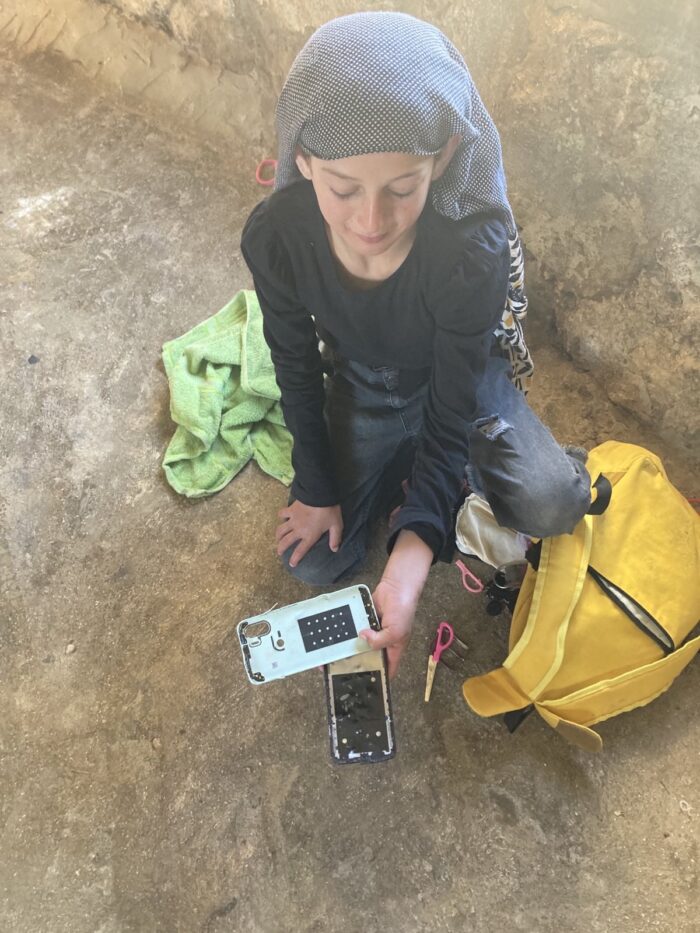

Not long ago he broke into the home of a family in Shi’b Al Boton and beat up the father while his seven young children watched in horror. Their mother tried to film the attack on her phone but Budi grabbed it from her and smashed it hard against the concrete floor. (In the image below, one of their daughters holds the remains in her hand).

Budi is the head of security at the Avigail settlement and has broad policing powers despite not technically being part of the IOF. As appointed security lead, he holds the power to detain and search any Palestinian, seize their personal belongings, and arrest them without warrant using any means necessary including force. His jurisdiction extends beyond the municipal boundaries of the illegal settlement and into privately owned Palestinian land.

He sat and stared at us until 7:30 or so before driving off past the outpost and into the bright lights of the settlement. We ate dinner that night hushed, listening for the sound of footsteps or tires on gravel indicating his return. He is the most frightening type of Zionist: all the authority of the army without any of the legal restraints. Part militant soldier, part lawless settler.

He came back the next morning. My comrade and I were woken up from deep slumber by the yelling of one of the daughters. “Mustawten!” She cried, pointing to the road behind the house. I had the wherewithal to pull on my boots but my poor friend bolted out the door barefoot. We ran up over the hill just in time to film a settler on an ATV chasing down a Palestinian shepherd’s flock. When he saw us he sped away but Budi appeared moments later in his white truck.

We ran back up the hill, the other volunteer trying his best to step on the flattest rocks and avoid the very prickly dry thistles. Again, we replayed the scene from last night. Budi stared at us and we stared back. An hour of strange silent moments passed before he left.

My friend informed me that Budi had attacked members in the Um Dorit family we were staying with as well. He told me that Budi was the one who destroyed their house, who cut down the grape vines, and who poisoned the well. No wonder the entire family was on high alert.

In the afternoon I swapped stations with two Israeli activists and stayed in Shi’b Al Boton at the home of the father who Budi attacked. It had been a few weeks since I was there last and it was so very good to see the parents and their seven beautiful children. I missed them so much that it took all my effort to staunch my tears. After three months of living closely with people, you begin to feel like part of their family too.

Lo and Behold, Budi came to their house both in the evening and in the morning. Still just staring, sometimes through binoculars and sometimes through dark sunglasses. It seemed like hours passed before he moved on. At one point the police came and talked to him but he kept up his patrol.

He drove back and forth, stopping for a small eternity in front of each of the six houses along the dirt road. At one point a young boy with Down Syndrome, who loves to make people pose and pretend to take their picture, walked right up to the white truck, not understanding that Budi was not a good person to talk to. We all held our breaths as his mother pleaded for him to come back.

Thankfully, this time, nothing happened. We rejoined the family on the flattened cushion on the floor of their communal bedroom to pick at breakfast even though all of us had lost our appetites.

But this is Budi’s goal. Terror. Terror made more visceral by the unpredictability of its embodiment. He wants to keep people on edge and scared. He is often successful.

Go here to learn more about settlement Civilian Security Coordinators (CSCs) and how civilian security squads function in the occupied West Bank.